Pemba, Tanzania: My Island Frenemy

Processing my time on Pemba, the wonderful island that almost killed me

While writing about my 2010 hospitalization and recovery, I indulged my urge to write more about the context in which I got so sick. I am conscious of my position as a White American writing about East Africa. My ability to leave the island to access higher-quality medical care was a privilege that few Pembans could afford. My goal in writing is to process my experiences, and while not attempting to speak for Pembans, I want to dismantle stereotypes rather than reinforce them, demystify rather than exoticize, and invite the reader to empathize without pity.

I visited Pemba in 2001, 2006, 2008, and 2010, staying anywhere from a weekend to several months on each trip. My master’s thesis focused on the island, and I read every dissertation, thesis, and article I could find to better understand the island’s people, history, culture, health, and politics. By the 2010 stay, when I became deathly ill, I had an MA in African Studies and a Master of Public Health. I had paused the first year of my doctoral studies to move to Pemba for nine months. I’d been studying and speaking Swahili for 12 years and had lived in Zanzibar for over a year.

Knowing I’d always be an outsider, I tried to immerse myself in Pemban life, to understand the culture, ways of living, ways of seeing the world. I found great joy when I spoke Swahili and for a few seconds, until they saw me, they thought I was local.

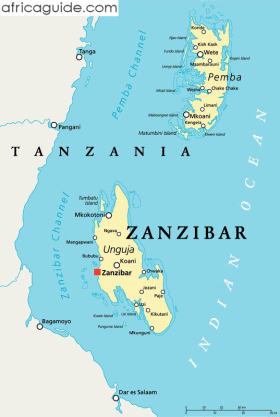

People have at least heard of Zanzibar, but few know about Pemba, the sister island to the north. Pemba is just as big in square mileage, and due to geological, oceanic, colonial, economic, and post-colonial political forces, Pemba is extremely poor and deliberately underdeveloped. Pembans mostly survive on subsistence farming, fishing, and wage work on large farms that produce coconut, rubber, and cloves.

Find Pemba on the map. Pemba is part of the semi-autonomous island region of Zanzibar, which is part of The Republic of Tanzania in East Africa.

The Zanzibari population is over 90% Muslim, and Pemba has an even higher proportion of Muslims. The few Christians who live there were considered outsiders, guests, strangers—wageni—even if they’ve been there for generations. You can’t truly be Pemban unless you convert to Islam, I was told.

Visitors on Pemba Island

Unlike Zanzibar, whose many beautiful white sand beaches attract tourists year-round, Pemba’s coast is mostly rocky cliffs and mangrove swamps. Very few international visitors make it to Pemba. It takes a certain type of mzungu (foreigner of European descent or a Westerner in general, regardless of skin color) to trek all the way to Pemba. First, you have to get to Tanzania. From the US, that usually means an 8-hour flight to somewhere in Europe or the Middle East, then another 8-hour flight to Dar-es-Salaam, TZ.

From there, you have to board a ferry (2 hours) or plane (20 minutes) to Zanzibar. Next, you take a much more run-down ferry to Mkoani, a small port town in the south of Pemba, or fly by tiny prop plane to Chake Chake, in the central area. Like, prop planes with 4 to 6 seats, including the pilot. When I lived there, the ferries ran maybe three or four times a week, and the flights twice a week. The airport is tiny, one building with one runway. Demand is so low that no taxis queue outside, waiting for passengers.

The occasional scuba diver, archeologist, public health scientist, missionary, or doctoral student showed up. I lived in Chake Chake. It’s a colonial-era town; the name translates roughly to “every man for himself”—which reflects imported colonial economic values.

White people were rare enough on Pemba that people told me, “I met another mzungu once. She lived in a village [an hour away] for two years. She covered her hair, like a Muslim. She was great.” Or “Oh, Bruce? Yes, we love Bruce. He left in 2005, though.” (I actually knew Bruce). One Peace Corps volunteer (Michael?), who was based in Mkoani, fell in love with a local young woman, converted to Islam, married her, and stayed. I met them once, not long after their wedding. I also heard a tale of a Christian missionary family far in the northeast of the island (“Do you know them?”), beyond where the tarmac ends, where anemia and malnutrition are the worst. But I never met them. Oh, and the Dutch-Turkish/English couple who ran a scuba diving hotel in the far northwest, past Ngezi forest.

My housekeeper, Maisha (pseudonym), once arrived at work marveling, “Watalii weeeeengi leo! Wanne barabarani!” There are so many tourists today! I saw four on the road!

Maisha

While I lived there, I still lived as a woman; Maisha was one of my only connections to women’s lives, women’s spaces. Maisha—not her real name—means Life.

A common phrase is maisha magumu, life is hard, a Swahili equivalent to c’est la vie. It’s the phrase of people who have little control over their lives due to poverty and political structures. Maisha magumu is a shrug of the shoulders, Whaddaya gonna do? It’s not giving up. It’s not laziness. America’s Protestant work ethic links poverty with laziness, but that’s ideology, not truth. People in poverty tend to be very hard-working. Maisha magumu reflects doing the best you can with the circumstances you’ve got.

When I first started staying in Zanzibar in 1999, I was expected to hire someone to cook, clean, do my laundry. But the idea of hiring a servant made me uneasy. It felt so upper class, so un-American, a land of self-reliance. But again, that is ideology, not truth. In the US, a whole lot of people are involved in getting food on my table; I just don’t see them.

Over the years of learning Tanzanian economic and class structures, I saw that refusing to hire someone was selfish. If I could afford to hire someone, I should, rather than hoard my relative wealth. Following my values, I tried to treat every person I hired well. I paid them more than the going wage. I didn’t scold or yell at them like a lot of bosses did. I helped them with medical bills and school fees for their kids. My household earned a reputation as a good place to work, which made me happy.

That’s not to say I was perfect. I found Maisha annoying, actually. And in later years of living on the mainland, I had another housekeeper I didn’t get along with at first. Now, her daughter calls me bibi, grandma. I realize that my attitude towards them was 100% about me. It was my own discomfort with gender roles and resentment of the expectation that I should have been a housewife. But unpacking that can wait. Back to Maisha.

Maisha was born on the island and had never left, even to visit Zanzibar. Pemba has a couple of excellent white-sand beaches, but Maisha had never seen one. This wasn’t unusual. Once she finished eight or nine years of school, she couldn’t pass the test to advance. Or her family couldn’t pay the fees, investing them instead in her disabled brother’s upkeep and medical bills.

When her father died when she was 18 or so, leaving the already impoverished family without an income, her mother married Maisha off to the first man who offered a bride price.* She couldn’t afford to be choosy and married a Kenyan divorcé, Juma, who already had a little boy about my son’s age. But at least Juma was Muslim. Being a foreigner, though, he had a hard time finding work on Pemba since such things rely heavily on kinship and other long-term networks.

*Bride price is the flipped version of a dowry. Dowry goes from the bride’s family to the groom, to help support the bride. Bride price goes from the groom’s family to the bride’s family (or the bride herself) to make up for the loss of her contribution to the family. If she divorces, she/her family is supposed to get the bride price back. Many Americans balk at this concept, seeing the sexism in “buying” a wife. Another way to interpret this: in cultures with dowry, the bride is seen as a liability, a burden. In cultures with bride price, she is seen as an asset. Since the bride price is usually too high (in money and goods) for a man alone, he must rely on his family to contribute. This means kinship and family relationships are key in men’s lives.

Maisha was somehow related to a man, Juma—a different Juma—whom I’d met during my first trip to Pemba in 2001. Juma was as popular a name as David + John + Michael in White America; I knew a lot of Jumas. This Juma drove a taxi, so I referred to him as Taxi Juma. Because cousins are often called siblings, aunts called Mama, uncles called Baba, and relative (ndugu) can also mean “someone I grew up with” or comrade (in the communist sense), I never did work out how Maisha and Juma were connected by blood, marriage, or affinity. Anyway, they were related enough that it was appropriate for them to interact with each other—a man and a woman—without it being suspect or scandalous.

When I stayed in Pemba in 2006 and 2008, Taxi Juma recommended that Raymond and I hire Maisha as a cook and housekeeper. Not because she had any particular skill or experience beyond any Pemban girl raised doing chores and cooking, but because he knew how poor Maisha and Kenyan Juma were.

At the end of my 2008 trip, Maisha invited me to her house for a quick visit. She’d been working in my house all this time, a guest, and she wanted to reciprocate in some small way. The visit broke my heart, understanding in a different way how much poverty she endured. But I kept my decorum and was a good guest in the Pemban way. I removed my shoes before entering, sat on the mat she laid out, and accepted a glass of juice she’d made. She explained she made the juice with bottled water. She teased me, saying it’s because wazungu have weak bodies and the local water makes us sick. I laughed at her joke. I praised her house. I praised her juice. I left a little money to cover the cost (a normal custom in Pemba that was rude in Zanzibar).

Her little family of three lived like far too many Pemban families: in a one-room, thatched-roof hut with a dirt floor. The floor was hard-packed from being lived on, and every morning and evening, Maisha swept it clean of loose dirt, bugs, fallen rice, and leaves. The hut’s frame was thin sticks tied together with homemade coconut-fiber rope and packed with red mud. If I remember correctly, Kenyan Juma built it for them.

They had no electricity but did own a kerosene lamp that someone probably gifted them for their wedding. Or perhaps she mentioned she didn’t have one, and I sent her home with one of mine. They had a lamp, but they usually couldn’t afford kerosene. At the end of her work shifts, Maisha would ask me every now and then if she could have just a little kerosene, like an ounce, just pennies’ worth. “I’d never want to steal any. I want to ask,” she’d say. I’d thank her for asking and send her home with several ounces; to me, it was maybe three or four dollars. To her, it was days’ worth of light after 6:30 sundown so her son could finish homework and a splash of fuel to light her tiny cooking fire to prepare dinner.

All land in Tanzania is owned by the government and leased to citizens, which barred Kenyan Juma from acquiring any. Plots to build or farm may be allocated through paternal or maternal kinship networks, but again, as an mgeni, he had none. But leave a plot open for long enough, someone is going to start growing something on it. Or they’ll build a temporary hut, like Maisha’s husband did. Their housing situation was precarious, both because they didn’t lease it and because it was right at the edge of a steep ravine.

Maisha and her family didn’t have a toilet, not even a pit latrine. Maisha was not alone. At that time, around 40% of Pembans had no toilet, not even a latrine. In the daytime, she used the pit latrine built off the courtyard of my place, and her son could use the ones at school. But at home, she had no such luxury. Maisha didn’t know anyone in her immediate area well enough to ask them to use their latrine—if anyone even had one. Instead, day or night, rain or shine, she’d descend the steep slope of the ravine into the bright green foliage, trying to find a spot private enough to squat and do her business. Afterward, she’d need to clean up using water and her left hand, and maybe some leaves. (Most Pembans, as most Muslims, don’t use toilet paper.)

As you can imagine, she felt embarrassed and worried that some young man might try to peep—or worse. Or that a snake, scorpion, or another creep-crawly-bitey thing might join her. Once, when she arrived for work in the morning, I mentioned the violent rainstorm we’d had during the night. The wind and rain hitting the metal roof had kept me up. She countered with her own story: she’d had diarrhea that night. She had to trek down the ravine in the dark in the heavy rain multiple times that night.

I found her personality annoying most of the time, which I still feel guilty about. But in these moments, my heart broke for her.